When owning nothing makes you happy

An injunction to know thy enemy.

If you quote Sun Zi you are gay.

Simple as.

It’s the literary equivalent of claiming that Mozart is your favorite composer. Those who actually listen to enough classical music for it to actually mean something are so heavily removed from the social mainstream that they constantly have to signal their special status, and that means they can’t have generic favorites like Mozart, no, they listen to the real stuff: Guiseppe Verdi, Richard Strauss and William Byrd (All of whom I just derived from a 30-second internet search)

So I can’t possibly quote Sun Zi. I have to quote something that sets me apart. Something displaying my good taste, something avant-garde, something esoteric something that separates me from the common schmuck down the street and signals my authority as a superior intellect. Something so niche that its name alone will have you set out on an odyssey of internet rabbit holes.

Hey kids! Have you ever heard of…

Carl von Clausewitz?

Friction

Clausewitz’s concept of friction, a summation of all things that separate the war-on-paper from the war-as-it-actually-plays-out, is a perfect supplement to Sun Zis “know thyself and thy enemy”. Where Sun Zi gives only a general notion, Clausewitz gives actionable metrics that give us a roadmap towards achieving said knowledge. The sources of friction are:

Insufficient knowledge of the position and intention of its enemies

unsettling rumors

Uncertainty over the strength and position of one’s own troops

Overestimation of difficulties and underestimation of one’s own capabilities (mainly in troops and lower officer ranks)

the difference between expectation and reality

the difference between strength on paper and actual strength

supply chain issues

the danger to be overwhelmed by first encounters and to “sacrifice ripe thought to the first impression”

I am pleased to announce that the dissident right, in its current struggle against the moloch of western civilization, is in fact not experiencing supply chain issues.

The task of getting the right to overcome the other 7 points however is in many ways herculean and not something I would ever try to seriously tackle on substack, not in the least because I am simply unable to provide guidance to such an extent. Yet I hope that I will be able to provide small contributions to points 1,2,4,6 and 8 as I currently see much of the discussion on the relevant issues falling into a sort of intellectual entropy.

3 and 5 come before 1 and 2

Before addressing the enemy, however, I want to address the source of this entropy. This relates more to points 3 and 5. The dissident right comes out of a recent cultural current where rightwingers understood themselves to be blanketly intellectually superior to their liberal opponents. Many right-wingers, especially dissident right-wingers, still believe their movement to be primarily academic in nature. This is decidedly not the case. The dissident right is a sociological phenomenon. It is a collection basket for those who got kicked to the curb by wider society. It mainly recruits from people who are down on their luck in their careers, from losers, from people who fled into video games, from kissless virgins, and anime addicts.

This is not a bad thing. Especially in an age where many have to choose between worldly success and keeping their sense of dignity and integrity, where commitment to a social group often stipulates the participation in some form of mass psychosis or another. It just has to be recognized. The DR’s primary function is giving a home to the homeless and a group to the friendless. That is why its members are so willing to watch hour-long streams, be it on cozy.tv, youtube, or odysee, where a known set of personalities waxes on about topics that perhaps need 30minutes of real attention.

Only when this need is addressed can we start talking about the other side.

Trust is an equation

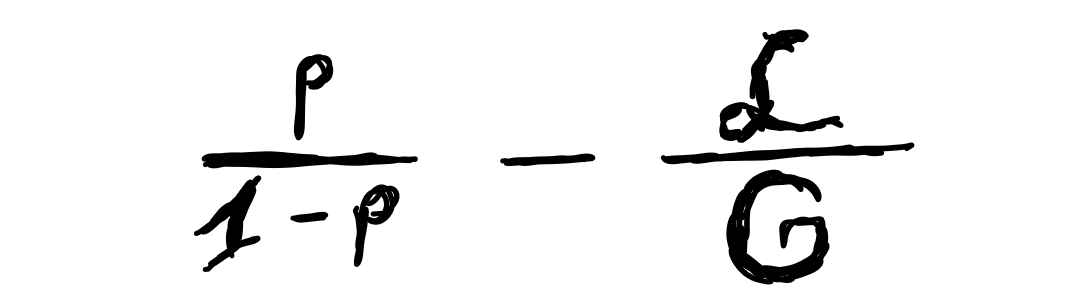

If money is the lifeblood of economics, trust is the lifeblood of social theory. Trust is the minimum factor onto which social relations can be broken down, where groups exist, there must exist trust. The funny thing with that is that we can break down the tendency of a person to invest trust in another with a simple equation:

(See James S Colemans “Foundations of Social Theory” p.99)

Where:

p - chance of receiving gain (the probability that the trustee is trustworthy)

L - potential loss (if the trustee is untrustworthy)

G - potential gain (if the trustee is trustworthy)

We trust someone if the value of this equation is greater than 0, are indifferent if the value is 0, and distrust if the value is less than 0.

Some of my readers may be appalled by this equation. It implies trust is an impersonal, self-centered calculation that has little to do with the other person outside of what can be essentially described as a CV. Good, keep this for later.

The more important part, for now, is that all three, p, L, and G are subject to various forces, most centrally various forms of deprivations. When we have few human connections we adjust p upwards. The more isolated we are the more we are willing to put trust in others. L and G are dependent on how deprived we are of money. L increases as our financial situation decreases, whilst G is proportional to our wealth. Fat Cats care little for gaining another 100k, even if it comes with high certainty, whilst starving Dogs are willing to gamble a lot on just gaining an additional thousand bucks.

A good illustration of this dynamic might be its abuse in the world of scam emails. Scam emails have certain characteristics in common. One of these being the initial e-mail, an outrageous claim, based on an even more outrageous story, written with typos. This is a feature. It pre-filters people who aren’t desperate enough to want it to be true. The people who write back will be sufficiently isolated that their p is highly inflated. In fact, the victim may see in this a cosmic justification for his isolation. He had to suffer so that he would be disproportionately rewarded by getting percentages of a king’s treasure. A perversion of man’s salvation instinct.

In the eye of a lover

Love is decidedly a concept too complex for the substack and completely reserved for the YouTube channel. So we will only cover the very basics here. Let’s look at Genesis 4:25 for example:

And Adam knew his wife again; and she bare a son, and called his name Seth: For God, said she, hath appointed me another seed instead of Abel, whom Cain slew.

Why does it say Adam knew his wife? It is fairly obvious that we’re talking about sexual intercourse here, and indeed, some translations of the bible will spell this out plainly: Adam had sexual intercourse with his wife. But the author of Genesis very consciously used the word knew. Why?

To understand this I first want to showcase two different ways this could have been spelled in modern English:

And Adam fucked his wife, and she bare a son…

And Adam penetrated his wife, and she bare a son…

On a technical level, these are fine, both contain the fact that Adam slept with his wife but, as I have mentioned in my video on language: Words often signify more than we intend them to:

So let’s see what fucking someone also entails. We say we fucked someone when we triumphed over them. We hatefuck, we say fuck you, we fuck around, fuck up, fuck off and when something goes badly we say “oh Fuck!”. It is a foul word and those who know me might even be surprised how liberal I am in its use here. If Adam had fucked his wife then the resulting son can only be seen as a bastard, as his triumph against her, as an imposition of his will against hers, as a product of rape.

A similar outcome is produced by “penetrating” the wife. Penetration, best made manifest in syringes, obelisks, lock picking sets, scalps, and hacking attacks, treats the other like a machine or a textbook. Things we penetrate we do not have to take in fully, we simply enter to fulfill our objective and then pull out again.

Knowing, however, before being turned into a form of mental penetration during the “enlightenment” era, used to have a very different meaning in the ancient world. A meaning that was for example described by Jurgen Moltman:

The motive that impels modern reason to know must be described as the desire to conquer and dominate. For the Greek philosophers and the Fathers of the church, knowing meant something different: it meant knowing in wonder. By knowing or perceiving one participates in the life of the other. Here knowing does not transform the counterpart into the property of the knower; the knower does not appropriate what he knows. On the contrary, he is transformed through sympathy, becoming a participant in what he perceives.

In sexual terms, this love means participation so deep, so intimate, that it turns into the melting together of two beings. The resulting child becomes an enfleshment of the couple’s love for one another.

But this “knowing” doesn’t necessarily imply sexual intercourse. In the old world’s sense of knowledge parents know their children but of course, don’t sleep with them. In fact, traditionally the term love was much more commonly used than it is today. Men loved each other deeply and enduringly for example, which, however, had nothing to do with sodomy.

From all this, it hopefully becomes clear how deeply loving someone, or knowing them makes one participate so extensively in the others being that it enables one to exert the exactly appropriate amount of trust towards them. So love is able to generate trust, but is trust able to generate love?

A world without emotion

The sad reality is that for a basic trust level we need to know very little about the other. And for a society to function we only need a basic trust level. We need to know what makes others tick, what animates them, but we don’t need to know them. This is already an uncomfortable thought, but to understand the true extent of it we first need to familiarize ourselves with a man called Edward C. Banfield.

Banfield had the terribly daring thesis that Italy may be a good country to spend his Holidays in. Or maybe he won a trip there when competing in America’s “Most generically American name” contest. Or maybe he had to pay off his debts to the mob in person. Regardless of the reason, the man made it into the beautiful town of Chiaromonte in the Basilicata region and thought it was…

terrible.

So terrible in fact that in the book he wrote about how terrible the town was “The Moral Basis of a Backward Society“ (1958) he didn’t use the town’s real name in order to protect it. Ouch!

And Banfield isn’t a common Schmuck either. His book would land him an advisory position in both the Nixon and the Reagan administrations. So what’s his problem with the people of southern Italy?

Family.

One of the crowning achievements of Banfield’s sociology was the concept of Amoral Familism, the idea that strong family ties prohibit the formation of trust in wider social settings as each family only trusts its own members and not those of other families. What was seeping into the halls of American policymakers was essentially the idea that families are the enemies of free markets.

Needless to say, Banfield has garnered a lot of detractors, my favorite being E. Ferragina who in 2009 wrote the beautiful sentence: “Theories that won’t die are those that confirm our most basic assumptions” which, whilst serving as a good critique of Banfield also tears down the entire concept of modern science as part for the course.

In the end, however, Banfield’s concept of amoral familism would reign supreme. It was confirmed by our boy J. C. Coleman and, more importantly, also confirmed in a trust experiment conducted by John Ermisch and Diego Gambetta in 2010 called “Do strong family ties inhibit trust?”

I quote directly:

“In particular, our results support the hypothesis that people with weaker links with their family are more likely to trust strangers. This suggests, counter-intuitively, that a decline in family connections typical of modern societies could not so much make for a more trusting society directly, but encourage people to take risks and discover through experience the real level of trustworthiness in their community, which if higher than they thought would raise their trusting expectations and their trust in strangers. What the mechanism is that explains this effect we cannot be certain. Yamagishi’s hypothesis, that this is because people with strong family ties feel more insecure in a social environment lacking mutual monitoring and sanctioning of social interactions, does not seem to be compatible with our results. These suggest that the difference in trust levels, between those with strong and those with weak family ties, is explained by the latter’s greater outward exposure: trust is positively affected by any factor that promotes the experience of the behaviour of others beyond one’s family circle. People who interact more with strangers and who have stronger motives to take risk with strangers appear to be more likely to trust because, if their experiences are predominantly positive, their expectation that people will be trustworthy is higher. In this sense, the expectations of people with more outward exposure should better reflect the level of trustworthiness in their ‘community’ outside the family. This suggests that people with weak family ties are in an equilibrium sustained by their better knowledge of others’ trustworthiness. In contrast, those with strong family ties sustain an equilibrium with limited interactions with strangers by their strong commitments to other family members.”

Ermisch and Gambetta are at an impass. They try to sugarcoat it but their experiment was solid. Its results are incontrovertible, and from the depths of the Erlenmeyer-flask a silent voice springs forth:

“If you want a modern society, turn people into rootless automatons, who have no choice but to trust each other.”

What does this make of us?

The dissident right identity is not a choice. We were cast aside and have trouble fitting in with people who are so obviously glued to a stream of endless lies that it is hard for us to get past five words of Smalltalk without getting into an awkward conversation. Many of us are the products of broken families, in countries with divorce rates so high the paperwork could be used as a space elevator if stacked. Most of us went to the internet in order to find someone to connect to. Most of us don’t have a choice but to stick together, to “trust” each other.

But for real trust, such a situation does not make. Real trust is an accident of knowing each other and we are mostly Anonymous.

And it is that kind of trust that needs to produce an outgroup, someone to dislike, someone to hate, and that is why we demonize our enemies. This is where the intellectual entropy sets in, as long as we have something to call our common enemy we don’t have to do much thinking.

But hey! Wasn’t this article supposed to be about them anyway? When do we talk about Klaus Schwab?

Well, fear not my eager friend because….

ALAKAZAM!

I was talking about the WEF crowd the whole time!

Yes, I was talking about the Dissident Right, but I was also talking about our current elites. Let me explain:

A genius Start-Up

My Alma Mater is one of the top business schools in Germany. We aren’t part of the international A-Team but we have a solid footing in the international B-Team, got Europe’s best Master in one desirable category and our graduates go all the way up to the boards of Big Tech and institutions like the WEF. We even have the occasional lower member of a major bloodline show up. So my mates at Uni were exactly the type of people the DR would deem the enemy, the managerial elite.

Just like the DR, these are children from broken homes. You can tell it in the small moment when they push down on the gas of their Porsche in a 50km/h zone when they are melancholic during their party hangovers when they talk about their childhood, sometimes they even just outright tell you. There are very few people in elite circles who have an actually stable family situation going on.

But where the DR rages against this machine, the managerial boy embraces it. He lives a lifestyle of noncommitment, he has a girlfriend for one night and another for another, he lives in Chicago and Paris and Singapore and Shanghai and Milan and Stockholm and Frankfurt before he turns 29, if he doesn’t change his job every 5 years he feels like he’s stuck on his career journey. Everything is for rent, everything is commodified, and so my peers cheered on a genius business idea that took part in the pitch competition at one of our student-hosted start-up congresses: Furniture for rent.

You will own nothing and you will be happy

This is the idea behind the, frankly retardedly phrased “You will own nothing and you will be happy” line touted by the WEF until the backlash on it got too hard. In fact, the very occurrence itself shows the problem with the WEF, the original sentence was very likely “You will rent everything” which some subcommittee looked at and said “people don’t understand the upside of this” and changed it to “You will rent everything, and be happier for it”, which a second subcommittee looked at and said “it’s missing impact” finally getting us the slogan we love to hate.

But regardless of how the slogan was created, it is not the howling bell of a world of communism, but one of a world of non-commitment. Rented furniture in rented apartments with rented cars and rented streaming services to supplement a job that can be quit at moment’s notice. No more roots, no more families, no more traditions, an endless suave of golden bodies running down golden beaches basking in the golden sun and photographing each other with gold embroiled iPhones, held forever in their twenties by virtue of the most advanced skin care cream. That is the world where all humanity can be reduced to appropriate profiles: Tinder profiles, CVs, Credit Scores, Criminal records, fakebook pages an endless array of masks that can be put on and molded, within reason. That is the future the WEF is working on and no other because that is the life its members have learned to live and it’s the closest thing they know to love.

Final words

The DR and the young global leaders crowd are really two sides of the same coin then. Two birds pushed out of the nest and struggling to fly on their own, one thinking this act to be just, the other unjust. The lot of our times ultimately will fall across this line, whether those championing the family or those championing the corporation will win.